Creature Feature: Wonderful Whip Spiders

June 5, 2022

We're back with another Creature Feature! These are turning into full-blown literature reviews, i.e. I do a shitload of research to write them and they're taking me longer to do than I originally anticipated. If you're reading this, I'd really appreciate feedback on the format - are these essays too dense and formal? Do I need to chill out? Please let me know!

Another update of note: I've decided to start hiding images by default. I've retroactively applied this to the wasp post. I hope this change will make these posts more accessible (particularly given the types of animals I like to write about). Anyway, we now return to your regularly scheduled programming...

Today's Featured Creature is my favorite non-spider arachnid, the (misleadingly named) whip spider! Whip spiders are shy, clever, and complex bugs. What they aren't is interested in hurting people, contrary to what their appearance may suggest.

Whip spiders are the members of the order Amblypygi. They are also sometimes referred to as tailess whip scorpions. This is equally misleading because they aren't scorpions or whip scorpions, which also aren't scorpions. To date, Amblypygi boasts 155 different species. They like warm, damp climates (though some species live in deserts), and they like being sheltered under leaves, bark, or inside caves.

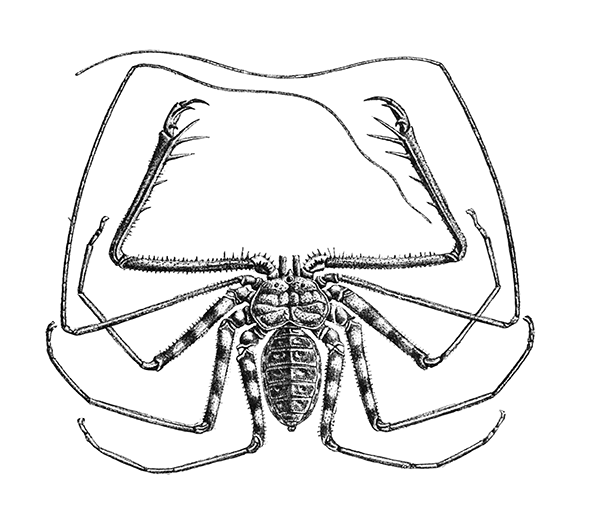

Amblypygids, like all arachnids, have 8 legs. This is not apparent when you look at them, because they only walk on 6. The front pair of legs, often referred to as the antenniform legs or whips, are antenna surrogates; they're several times longer than the body, and they're used for communication and sensing, not locomotion.

As if that wasn't enough limbs, whip spiders also have large pedipalps that resemble arms. This makes them look fierce, but they lack venom, so they usually respond to threats by running. However, they'll readily defend themselves if cornered. An angry whip spider may not be able to kill you, but its pedipalps can break skin, so antagonizing them is ill-advised.

Whip spiders had to go through the trouble of manufacturing antennae because they're chelicerates, one of two groups of arthropods that lack antennae. The whips are remarkably specialized; they have a ton of receptors that can pick up tactile inputs, smells, and even air particle movements. Amblypygids make extensive use of their whips in virtually every aspect of their lives.

Drawing of Damon johnstonii

Whip spiders tend to stay in one burrow for extended periods of time, and they're very good at finding their way back after they leave. In one study, whip spiders that were moved 10m away from their burrows all successfully found their way back in as few as 3 nights, with some making it home in one. They even make pit stops in temporary burrows (bug motels, if you will) on their way home, indicating that they may have more extensive knowledge about their environment than simple path recognition. It's hypothesized that the relatively large and elaborate brain structure of ambypygids contributes to their directional abilities. It's also been found that the whips play a critical part in navigation.

Once a whip spider has a nice burrow, it can be understandably reluctant to let it go. Territoriality is found in many amblypyigd species, and individuals of both sexes will fight to defend their homes. How far these fights go varies: in some species, fights rarely result in injury, while other species will fight to the death.

However, violence isn't inevitable; whip spiders prefer to talk things out first, so fights first consist of a series of behaviors that gradually escalate in aggression, with violence only occurring after all alternatives fail to resolve the conflict. The most dramatic of these is rapid vibration of the whips, which is sensed by the opponent's leg hairs without making contact. The information in these vibrations can determine the outcome of a fight before the first punch is thrown.

On the other end of the interaction spectrum, courtship in amblypygids is a lengthy affair, lasting from one hour to 8. Male whip spiders treat their mates to a variety of different behaviors, including whip vibrations, assorted jerking motions, cleaning, pedipalp extension, and even stroking her whips with his mouthparts. After the romantic gestures have concluded, the whip spiders mate externally.

At this point, the male is done, but there's still much to do for the female. She carries her egg pouch around on the underside of her abdomen. When they hatch, the babies crawl onto her back. Not all of her offspring will survive; there are a lot of eggs in a clutch, and only so much space on her back. Anyone who falls off faces certain death, and mom may even eat them.

Photo of a whip spider with babies

The babies that survive will remain clustered on their mother's abdomen until their first molt. This is already pretty intense parental investment, but in at least two species (D. diadema and P. marginemaculatus), moms will continue to live with and care for their offspring until they reach sexual maturity, which takes about a year. From Rayor and Taylor (2006):

Initially the adult female stood alone on a section of vertical bark. She made a directed walk into a group of ten closely associated offspring and gently stroked them with her whips. The young moved to surround and orient to her, and stroked her in return, touching her whip, pedipalps, and legs [...] Although the young initially had been sitting close together, slowly waving their whips, once the adult female joined the group the youngsters' whip movements quickened so that most of the young contacted one another as well as the female. [...] The interactions were deliberately initiated and appeared to be affiliative behavior between the mother and her offspring.

In D. diadema, siblings stop being so chummy with each other once they reach their ultimate molt, and adults will get into fights with each other if their personal space is invaded. On the other hand, adult P. marginemaculatus rarely behave aggressively towards other whip spiders they're familiar with, and they can even be found in multigenerational clusters. We have yet to see if other species have similar social behaviors.

Close-up photo of a whip spider

An unidentified whip spider in a cluster with other whip spiders.

There's still lots left to learn about whip spiders. Some topics of particular interest are their whip communication abilities, the origins of their sociality, and the extent of (and reason for) their intelligence. (I think we should start making them solve puzzles for treats.) I think they're the most incredible little animals, and their poor reputation among humans is completely undeserved.

As always, you can find a list of the papers I used here!